「ナイト・ミュージック」という伝説的TV番組を知ったのは、Bacharachと共演したアール・クルーがやっぱりサンボーンともご一緒しているのじゃないかしらと思って見つけた#111がそもそもの始まりだった。本当にすごい番組で、オサム・キタジマ(内藤洋子の配偶者で喜多嶋舞の父)がお琴を弾いているのや、ブルガリアの女声合唱の3人組トリオ・ブルガルカが出演していたりの驚くべき番組で、まだちゃんと全部は観ていない。

日本語の記事でよく「泣きのサンボーン」と書かれているのが腑に落ちなかった。そんなメソメソしてないやんか!と思っていたからで、このミルクマン氏の記事中の「the Sanborn squeal」は、「悲鳴」や「鳴き声」とか「きしむ」とか「キャーキャー」とかいう意味になるらしい。それで、あぁそれならあれやね!と分かった。

イーグルスとの共演は『One of These Nights』だけじゃなく『Sad Cafe』もあり、もっとあるかもしれない。

==============================================

デビッド・サンボーンの懐かしい思い出

A Fond Reminiscence of David Sanborn

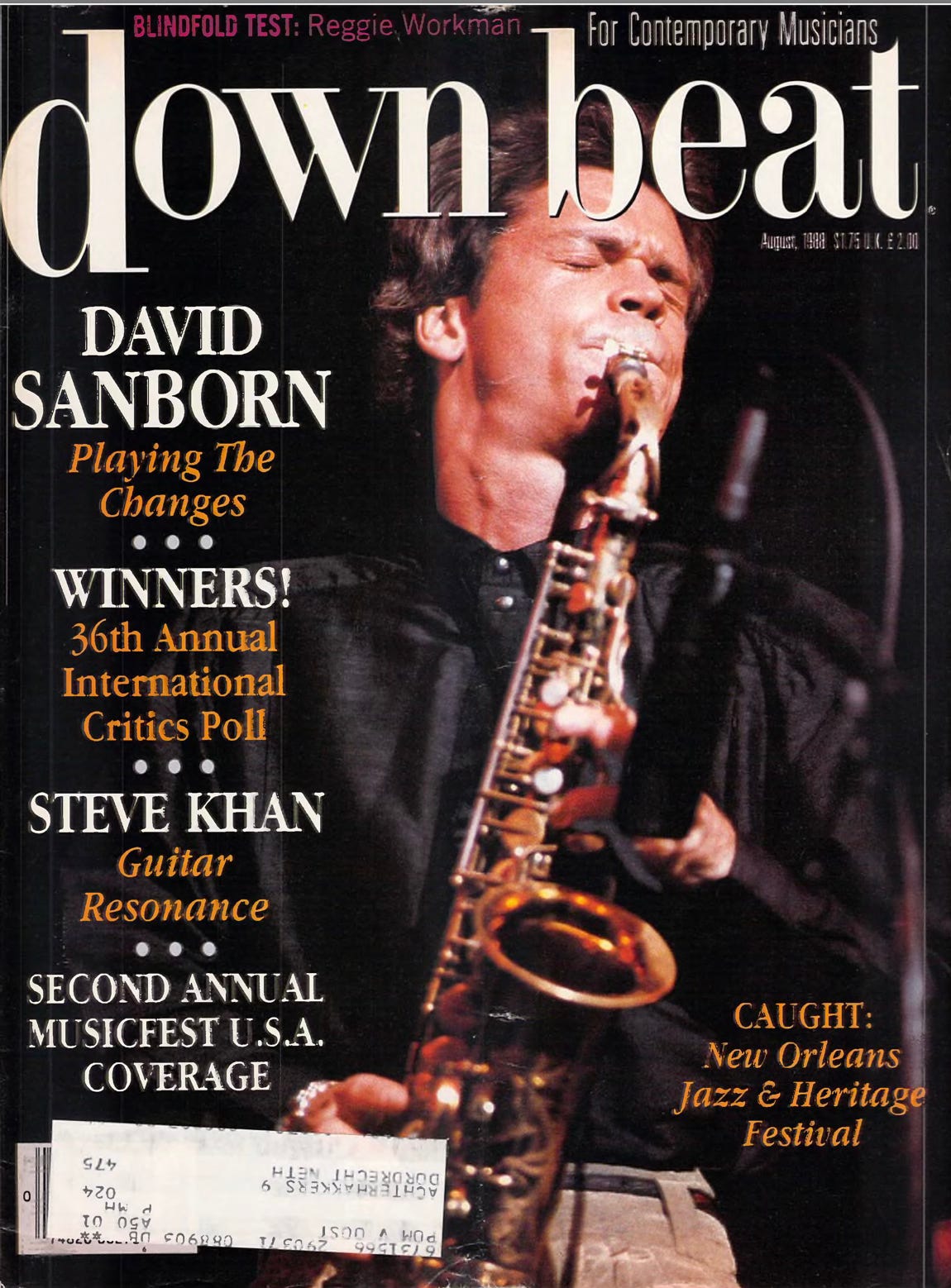

日曜日(2024年5月12日)に78歳で亡くなった偉大なアルトサックス奏者は、1988年に彼が芸術上の岐路に立たされていた時に、私が書いた『ダウンビート』の表紙記事の題材でした。

ビル・ミルコウスキー 2024年5月14日【Musings on Music by The Milkman:ミルクマンによる音楽についての思索】

https://billmilkowski.substack.com/p/a-fond-reminiscence-of-david-sanborn?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

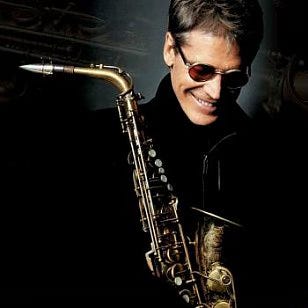

写真:アリス・ソイヤー

1975 年、ミルウォーキーの代表的なフュージョン バンド、スウィートボトムは、デビッド サンボーンの人気ソロ デビュー作「Takin’ Off」のほぼすべてのトラックをカバーしていました。スウィートボトムの演奏を聴くために毎週サルディーノズ ブル リング リミテッドに詰めかけた洗練された観衆の間で、そのアルバムに収録されているスティーブ カーンの「Butterfat」と「Duck Ankles」のカバーが特に好評だったことを覚えています。

Butterfat · David Sanborn

Taking Off ℗ 1975

https://youtu.be/rZcbic0FjWA

1975 年の同じ夏、ラジオではデヴィッド・ボウイの「Young Americans」が大ヒットし、サンボーンの代表的なアルトサックスの演奏が披露されました。そのリリースの直後に、サンボーンのアルトサックス、マイケル・ブレッカーのテナーサックス、ランディ・ブレッカーのトランペットがフィーチャーされたブレッカー・ブラザーズのデビューアルバムがリリースされました。

サンボーンのおなじみのアルトの叫び声は、その年、ポール・サイモンの『Still Crazy After All These Years』、ブルース・スプリングスティーンの『Born to Run』、イーグルスの『One of These Nights 』、マンハッタン・トランスファーのデビュー作『Manhattan Transfer』、ジェームス・テイラーのラジオで大ヒットした『How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)』、そしてフュージョンの金字塔『 Beck &Sanborn』にも登場した。

Joe Beck & David Sanborn – Spoon’s Theme

https://youtu.be/FxgdlIOa2bU

翌年、デヴィッドのアルトサックスは、ベースの天才ジャコ・パストリアスの1976年のデビューアルバムに収録されているファンキーな「Come On, Come Over」や、モーズ・アリソンの「Your Mind Is On Vacation 」、マイケル・フランクスの「The Art of Tea」、フィービー・スノウの「Second Childhood 」、ジョージ・ベンソンの「Good King Bad 」、ブレッカー・ブラザーズの「Back to Back 」、イアン・ハンターの「All American Alien Boy 」で聴くことができる。そして1977年には、ボブ・ジェームスとの初のコラボレーションアルバム「Heads 」を発表し、ジェームス・テイラーの「JT」、ドン・マクリーンの「Prime Time」、そしてギル・エヴァンスの「Priestess」(「Short Visit」ではサンボーンが圧倒的なソロを演奏)にも参加している。

Gil Evans – 2. Short Visit

https://youtu.be/4kqLbppLEuo

また、同年、3枚目のアルバム『Promise Me the Moon』をリリースし、大ヒットを記録した。ポール・バターフィールド・ブルース・バンド(1968年の『In My Own Dream』)、マディ・ウォーターズ(1969年の『Fathers and Sons』)、スティーヴィー・ワンダー(1972年の『Talking Book』』)、イーグルス(1972年の『Take It Easy』)、B.B. King(1972年の『Guess Who』)、トッド・ラングレン(1973年の『A Wizard, A True Star』)のレコードのホーン・レコードでサンボーン70年代の演奏を聴いていた。

Pharoah Sanders, David Sanborn, Night Music — ‘Thembi’

https://youtu.be/uTNR9hOR7ok

Sonny Rollins and David Sanborn play “Kim” – Live on Night Music – 1989

Taken from Night Music 119

https://youtu.be/hBARGhakXLw

Phil Woods and David Sanborn from Night Music, 1988

https://youtu.be/wAEdeXpVcpo

Sting – Bill Frisell – Dave Sanborn – Don Alias – Aint No Sunshine

Night Music 1989

https://youtu.be/zC2fPLxocHU

Eric Clapton – Hard Times

Night Music with David Sanborn

https://youtu.be/cGCxo2HLuYA

Hank Crawford playing “The Peeper” on Night Music

https://youtu.be/o0Cx8Tk4Miw

John Zorn, David Sanborn, Marcus Miller – Snagglepuss – 1988, Live @ Night Music

https://youtu.be/UXYkSlG9kcw

‘Night Music’ (‘Sunday Night’) show, season 1, episode 7, which went on NBC channel in 1988.

Curtis Mayfield – Pusherman [Sunday Night Live 1989]

https://youtu.be/6dTSIXcfT3U

Rufus Thomas – Walkin’ the Dog [Sunday Night Live – 1989]

https://youtu.be/BmLTAfUkAJ0

Bootsy Collins & Pretty Fat – Stretchin’ Out [Night Music 1990]

https://youtu.be/WNMJEvxqj_g

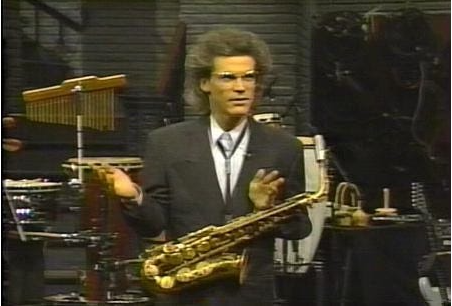

1988年から1990年まで、サンボーンはヒップなテレビ番組「ナイト・ミュージック」の司会を務めた。毎週日曜日の夜、さまざまなゲストがアメリカのテレビ画面をパレードし、サンボーンは有益な紹介を提供するだけでなく、バンドと一緒に座っていました。 ブーツィー・コリンズ、スティング、エリック・クラプトン、ルーファス・トーマス、ジョー・コッカー、アレン・トゥーサン、ディジー・ガレスピー、ソニー・ロリンズ、ファラオ・サンダース、フィル・ウッズ、ジェームス・テイラー、ヴァン・ダイク・パークス、スリム・ガイヤール、エディ・パルミエリ、ドクター・ジョン、スティーヴィー・レイ・ヴォーン、メイヴィス・ステイプルズ、サム・ムーア、アシュフォード&シンプソン、 ミルトン・ナシメント、ジャック・ブルース、ビル・フリゼール、アル・グリーン、エリオット・シャープ、ジョン・ゾーン、ポップス・ステイプルズ、ジョン・ハイアット、カーティス・メイフィールド、アビー・リンカーン、マリアンヌ・フェイスフル、フィービー・スノウ、フォンテラ・ベース、アーロン・ネヴィル、アル・ジャロウ、レナード・コーエン、クロノス・カルテット、彼の個人的なアルトサックスのヒーロー、ハンク・クロフォードなど。そして、サンボーンは彼ら全員に同席しただけでなく、それぞれの場面で自分の意見を十二分に発揮した。

1988年8月号の『ダウンビート』誌に掲載されたサンボーンへの最初のインタビューでは、成功という魅惑的な機械に巻き込まれることについて熟考していたが、その中で彼はニューヨークのアッパー・ウエスト・サイドにある彼のアパートで行われた。数年後、私は彼とボブ・ジェイムスが2013年にリリースした『カルテット・ヒューメイン』(スティーヴ・ガッドとジェームズ・ジーナスとの共作)に合わせて、共同インタビューを行いました。最近では、2021年に出版した私の著書『テノールの巨人への頌歌:マイケル・ブレッカーの生涯と時代と音楽』(Backbeat Books)で、マイケル・ブレッカーに関する非常に洞察力に富んだ(そして愉快な)解説を惜しみなく共有しています。この前の母の日(5月12日日曜日)に彼の訃報を聞いたとき、そのニュースは大量のレンガのように衝撃を受ける。彼は心からの笑顔、自虐的な機知、そして楽器の音色を一目で認識できる優しい男でした。RIPデビッド

一瞬でわかる――サンボーンの悲鳴。それで目隠しテストで誰も騙されていないのですか。それとも、そうでしょうか?

最近、サンボーンのクローンが大量に現れ、ポップジャズからテレビのジーンズのコマーシャルまであらゆるところで見かけられるようになったため、本物と模倣品を見分けることがますます難しくなってきている。ラジオのダイヤルやチャンネルセレクターをざっと回すと、商業ミュージシャンやアルト歌手志望者全員がサンボーンの音を真似しているように思えるかもしれない。しかし、時間をかけてよく聞いてみると、真実がわかる。

これはデイヴを困惑させ、苛立たせる状況だ。もちろん、音楽の歴史の中では、こうしたことは何度も起きてきた。バードのクローン、ウェスのクローン、チャーリー・クリスチャンのクローン、トレインのクローン、ジャコのクローンなどが登場してきた。だが謙虚なサンボーンは、自分をジャズ界の偉人たちと同じ仲間だと考えることを拒否している。実際、彼はジャズミュージシャンと呼ばれることにまったく不快感を抱いている。この男が混乱している、と言えば十分だろう。ワーナー・ブラザースからの11枚目のリリース――典型的にはファンキーでハードな吹奏感があり、非常によく練られた『クローズアップ』(マーカス・ミラーがプロデュース、レイ・バーダニが共同プロデュースとエンジニアリングを担当)――のリリース前夜、サンボーンはこう告白した。今、私に何が起こっているのか分かりません。私は知らないよ 。 。 。もしかしたら、それは中年の危機かもしれない、もしかしたら、私はただ完全に決別し、変化を起こす必要があるだけなのかもしれない。私は今、自分のやるべきことを少し見直しているところです。戻ってたくさんの音楽、主にビバップを聴くつもりです。ニコラス・スロミンスキーの『音階と旋律パターンの類語辞典』をよく使っています。モーツァルトのフルートデュエット、オリバー・ネルソンの本、ジョー・ヴィオラ・バークリーの本、フェイクブックも何冊か持っています。結局のところ、ただリサーチをしているだけだと思います。ただ脱皮しているだけです。」

文と文の間には長い沈黙があり、時折ため息が出ます。明らかに、この男は自分自身と対立している。この突然の心変わりから何が生まれるかはわかりません。彼は、ドラムマシンやスタジオ・マニピュレーションのテクノロジーから離れて、オール・アコースティック・コンテクストを取り入れ、昔のようにスタジオでライブで何かを録音することをほのめかしました。しかし、それは声に出して考えているだけです。あるいは、この考え方は共通しているかもしれません。あるいは、デイブは日/週/月/年が悪かっただけかもしれません。理由が何であれ、彼は突然自分の方向を推測しているが、クローズアップを聴いているだけではわからない。サンボーンは「Slam」や「JT」、「Pyramid」といったファンキーな曲で、典型的な信念と炎を吹き飛ばします。そして、サンボーンの特徴的な鳴り声は、「Goodbye」、ランディ・ニューマンの哀愁漂う「Same Girl」、そして数年前にヒットしたポップ・ラブソング「You Are Everything」など、魂を揺さぶるバラードで再び力強く戻ります。したがって、売れ行きが好調なサンボーンのホットなアルバムです。

我々はデイブがネルソン・マンデラの誕生日パーティーで演奏するためにロンドンへ出発する前日に、マンハッタンのアッパー・ウエスト・サイドにある彼のアパートで話を聞いた。その間、彼は引き続き「レイト・ナイト・ウィズ・デイヴィッド・レターマン・ショー」に定期的にゲスト出演し、ポール・シェイファー、ウィル・リー、アントン・フィグ、シド・マッギニスとともにハウスバンドを組んでいる。また、NBCラジオネットワークで放送されている彼の週刊番組「ザ・ジャズ・ショー」も引き続き放送している。将来的には、サタデー・ナイト・ライブのレギュラーであるデニス・ミラーと共に秋のテレビ番組の司会を務める計画がある。9月下旬から日曜の夜に放送されるこの音楽とコメディの番組は、仮に「サンデー・ナイト」と呼ばれている。ミラーや他のゲストと冗談を言い合うほか、サンボーンはハウスバンドを率いる予定だ。ハウスバンドには(この記事の執筆時点では)ベーシストのマーカス・ミラー、ドラマーのオマー・ハキム、ギタリストのハイラム・ブロック、キーボード奏者のドン・グロルニックといった素晴らしい才能が揃っている。しかし、それはまた先の話だ。今のところ、デイブは胸のつかえを晴らしたいことがある。シェイファー、ウィルリー、アントンフィグとシドマクギニスと一緒にハウスバンドで紹介デビッド定期的なゲスト出演を続けている」と呼ばれています

ビル・ミルコウスキー(以下、ミルコウスキー):楽器で声を出すことを可能にするために。

デヴィッド・サンボーン:ええ、それはいろいろな音楽の素晴らしいところのひとつです。それは誰かの個人的な声明です。最終的には、それが最終的に何になるかです。あなたは自分のテクノロジーを洗練させますが、目的は自分自身を作成することです。そして、表現するものが何もないのなら、表現する人格や人間性がないのなら、どんなテクニックを使っても何の役にも立たない。

BM:その点について、あなた自身についてどう思いますか?

DS:テクニックもないし、どんどん個性を失っていって(笑)。今、自分に何が起こっているのかわかりません。私はよくわからない移行を行っています。ですから、結果的に、これはうまく表現できません。

BM:しかし、あなたはますます、あなたのサウンドがすぐに識別できるという意味で、あなたの足跡を残してきました。

DS:そうですね…世間知らずだとか、謙虚だとか言うつもりはありませんが、そうだと思います。そして、私は自分のことをイノベーターだと少しも思っていないので、それについて考えるのは少し不快です。そう言われると、それが何を意味するのか理解するのが楽しいとなると思います。つまり、70年代初頭にポップスやR&Bのイディオムでアルトを演奏していたのは、たまたま僕だけだったんだと思います。デヴィッド・ボウイ(『ヤング・アメリカンズ』)やスティーヴィー・ワンダー(『トーキングブック』)、ジェームス・テイラー(『ハウ・スウィート・イット・イズ』)、ブルース・スプリングスティーン(『ボーン・トゥ・ラン』)などを通じて得た経験は、とても幸運だったと思います。だって、新しいことは何もしてないんだもん。特に新しいことや革新的なことをしていたわけではありません。僕はただ、僕が受けた影響を十分に抽出しただけなんだ。キャノンボールやフィル・ウッズ、ジャッキー・マクリーン、ハンク・クロフォードなど、僕が尊敬する人たちのようなサウンドを心がけていたんだ。

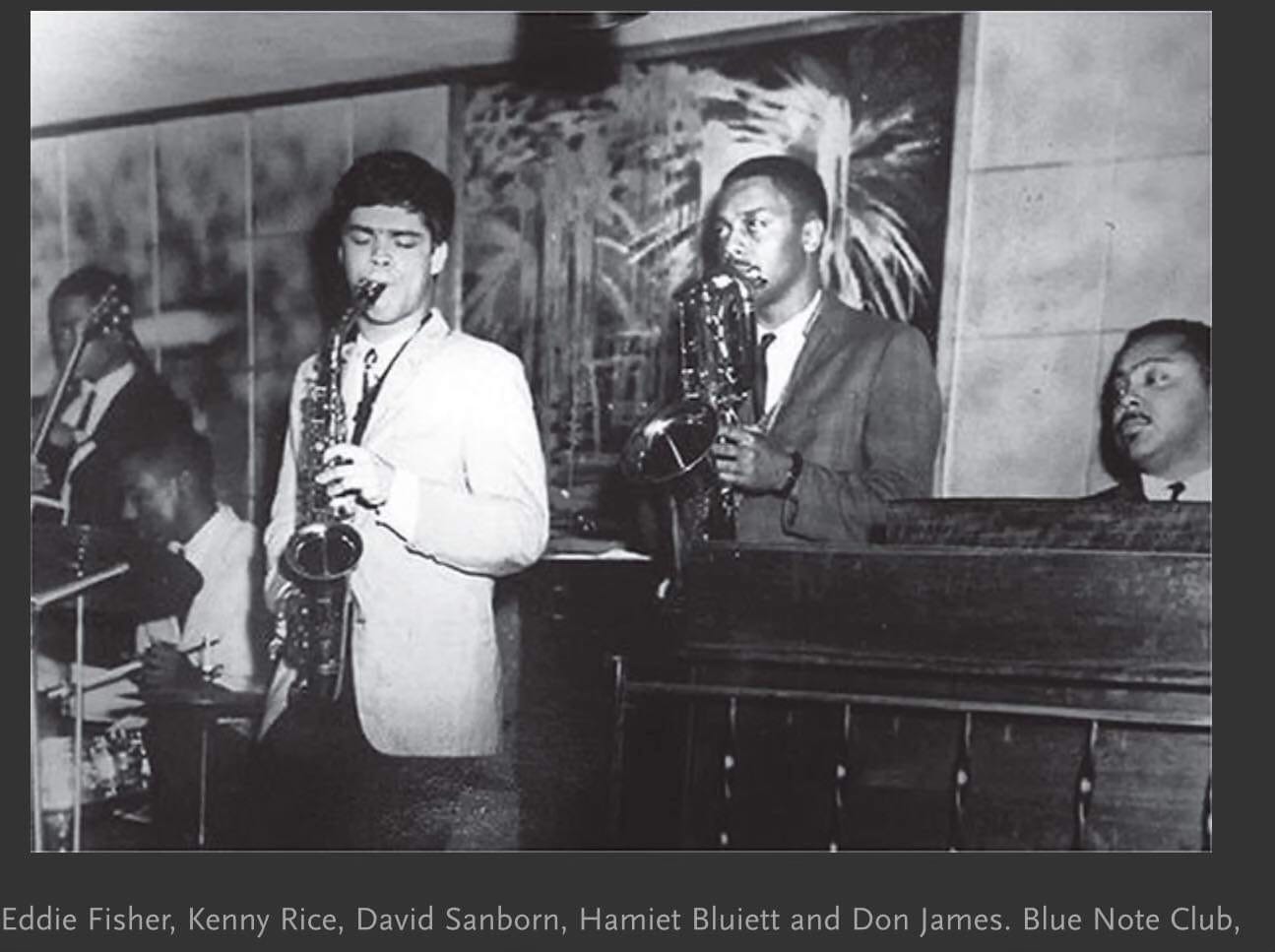

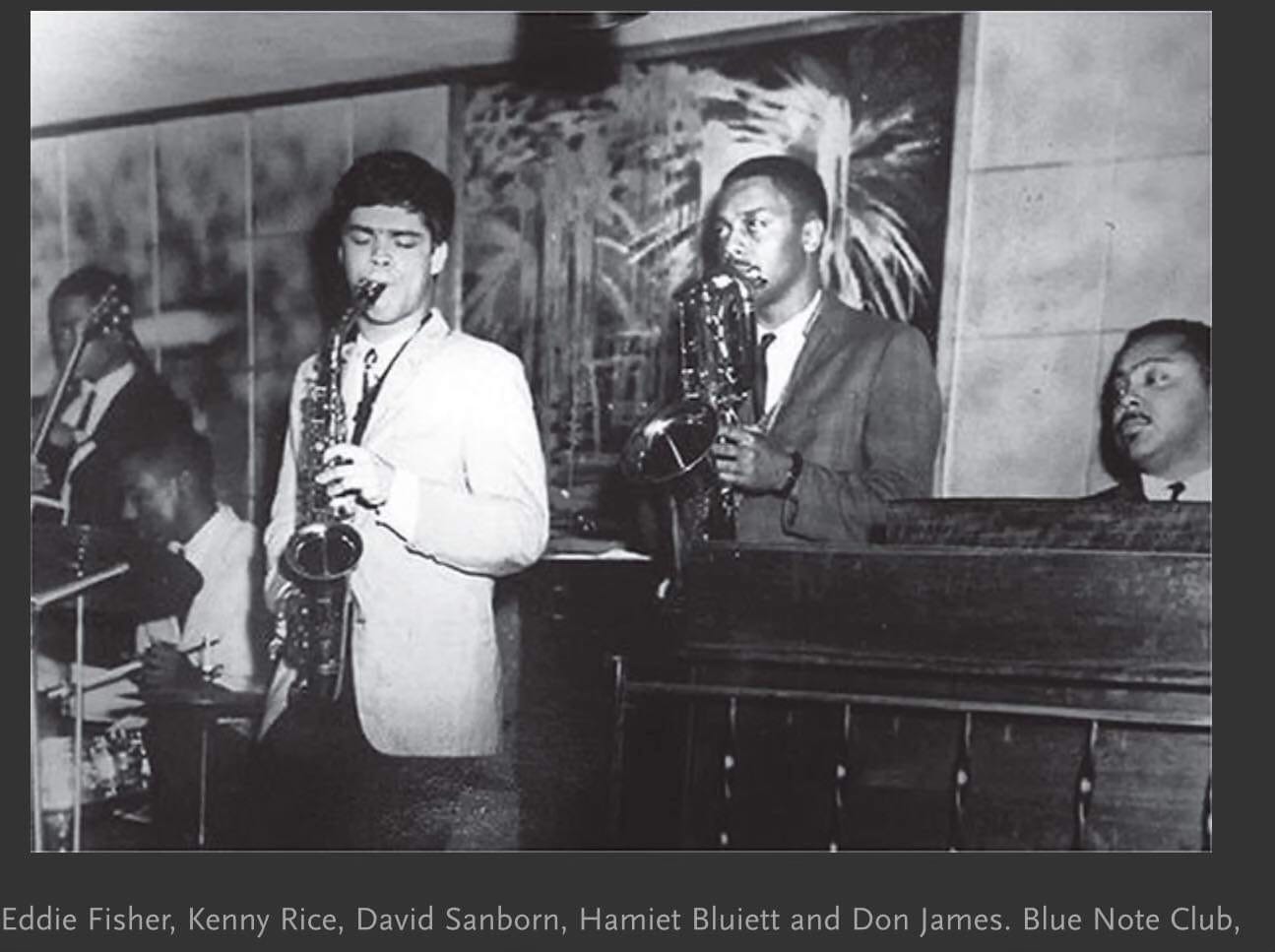

David Sanborn at age 16 playing in St. Louis with some experienced vets on the bandstand

16歳の時、セントルイスで貴重なベテランたちとバンドスタンドで演奏するデヴィッド・サンボーン

BM:しかし、あなたは何か、特徴的な資質を知っているでしょう。デヴィッド・ボウイのことは、「ヤング・アメリカンズ」のあのサックスを聴くまでは、あまり気にしたことがなかった。セリフではなく、音です。

DS:そうですね、それがプレイヤーとしてやるべきことであり、どんな形であれ、自己表現は自分自身を見つけるものです。あなたは自分のテクノロジーを洗練させていますが、出てくるものはあなたです。キャノンボールのようなサウンドを心がけたというのは、彼の演奏を聴いて、そのクオリティ、エネルギーをエミュレートするってこと。あんな舐めはできないからやれなかった。それは私ではありません。私がビバップ・プレイヤーではないのは、そういう理由だ。つまり、私はビバップのいくつかの影響を与えることができます、感覚に共感し、ある程度理解されていますが、それを演奏しているのは…なぜでしょうか。あなたは自分のイディオム、表現の焦点から一歩踏み出して学びます。あなたは学び、成長するために、他のことをします。しかし、あなたが戻ってくるのはあなたの…「アート」 こちらを使いたくないのは、自分のやっていることを必ずしもアートだとは思っていません。

BM:それはあなたの声です。

DS:ええ、あなたは自分の声を繰り返します。そして、あなたがどのような道を選ぶにせよ、あなたが世界に対して何を言おうと、それはその基本的なことに帰着します。それは、画家、彫刻家、作家など、深いです。ハンター・S・トンプソンとかジョン・アップダイクとか。それは彼らの声であり、彼らの視点です。もっと言い方をすれば、音楽とはそういうもので、世界に対する誰かの視点です。それはすべて彼らの影響であり、おそらくあなたはすべての影響を与えます。しかし、あなたはそれらの影響をすべて抽出し、うまくいけば、非常に無意識の方法で伝わってきます。あなたをあなたたらしめ、伝統とのつながりを与えてくれます。しかし、あなたの声は、その伝統についてのあなたの視点です。

BM:そして、自分の声を見つけたら、あとは適用、つまり文脈の問題になります。そして、レコード会社からアーティストにかかってくるプレッシャーは言うまでもなく、取り得る手段がたくさんある今日では、それは難しい決断になるかもしれません。

DS: ある意味、それは罠かもしれません。それは、多くのサイドマンやスタジオプレイヤーが最終的にソロレコードを作るときに起こることです。突然、彼らは「ねえ、私はここでこれとこれとこれを行うことができます」と言います。まあ、それはいいのですが、あなたはどうでしょうか。あなたがジャズ、ロック、R&B、その他何でも演奏できることは知っていますが、その中であなたはどこにいるのですか?ですから、コンテキストを実際に物理的に作成するか、マイルス・デイヴィスのように単に生成するかにかかわらず、コンテキストを作成することが重要だと思います。つまり、マイルスは曲を書くのではなく、音楽を作るのです。ウェイン・ショーターがマイルズのためにすべての音楽を書いていた時代、それはまだ正真正銘マイルズの音楽であったことに疑いの余地はありません。ウェインが曲を書き、原材料を提供したにもかかわらず、マイルスが文脈を形作った。そして私はマイルスと仕事をした数回でそのような経験をしました。ギル(・エヴァンス)も同様だ。彼らは両方とも声の背景を作成するアレンジャーです。ギルがマイルスと『ポーギー・アンド・ベス』の編曲を行ったとき、ギルのアレンジメントは多くの場合、ガーシュインのピアノの楽譜をオーケストレーションしただけであったにもかかわらず、ギルの編曲となった。彼はこう言った。しかし、それを彼がどのようにオーケストレーションし、どのように音楽を形作ったかが、それを彼の個人的なステートメントにしたのです。そして、彼がその特定のスコアを選択したという事実も、文脈を形作るのに役立ちました。それらすべてがそこに含まれています。ただ遊ぶだけではなく、遊ぶことはたくさんあります。それは…今は自分自身で、全体、プロセス全体を再評価する必要があると思っています。

BM:では、どんなことを考えているんですか?

DS: これから自分が何をしたいのか、少しずつわかってきたところです。イディオムで何をするかは考えたくない。私自身の行動の結果、そして他の人が私を真似した結果、私がやっていることは非常に様式化されたように思えます。つまり、それらを聞くと少し当惑します。そして多くの場合、彼らは私よりも優れたプレーをし、私よりもはるかに高い技術的能力を備えています。私のサウンドをマイク・ブレッカーのテクニックで作っている人もいます(笑)。そして、彼らは優れたプレイヤーであり、サウンドの面だけでも、人々が私に影響を与えたと考えていることを光栄に思うべきだと思います。サウンドに関して、私がプレイヤーに与えた影響はここにあると思います。

BM:お世辞を言うかもしれませんが、copycat(盲目的にまねる)こと全体に警戒心を抱いています。

DS:ええ、そういうのはあまり聴きたくないんです。時々ちょっと気が散ることもありますが、気にしないようにしています。自分自身に「ああ、もうちょっと違う音にしなきゃ」なんて言いません。特に、誰かがレコードで私が犯した間違いを真似しているのを聞くと、すごくおかしくなります。ある男が…名前は言いませんが…本当はこう言うべきではないのですが…いや、忘れてください。

BM:ジョン・コルトレーンやチャーリー・パーカーを真似した、あるいは真似しようとしたサックス奏者はたくさんいます。

DS:ではでは、テナー奏者でありながらジョン・コルトレーンの影響を受けないなんてありえるでしょうか。あるいは、アルト奏者でありながらチャーリー・パーカーの影響を受けないなんてありえるでしょうか。

BM:同様に、1988年にアルト奏者志望で、デイヴィッド・サンボーンの影響を受けずにいられるわけがありません。

DS: ええ、でも違いは、チャーリー・パーカーは革新者で天才だったのに対し、私はただ…私にはプレイスタイルがあるということです。チャーリー・パーカーは、リズミカル、ハーモニー、メロディーの面で革新者でした。彼は楽器に革命をもたらしました。そして音楽。そして、つまり、私は面白いサウンドを思いついた人に近いので、それで生計を立てることができて幸運なことに、人々が私を雇いたいと思ってくれて、私が演奏し、その方法を学び続けることができるようになりました。私の楽器をもっと上手に演奏してください。しかし、それは…つまり、同じではない…私とチャーリー・パーカーを同列に言うことさえできないでしょう、なぜなら、彼のしたことと私のしたことの間には深淵があるからです。私はたまたま心地よいサウンドとスタイルを持っているだけです…私は決して革新者ではありません。そして、私は自分を卑下しているわけではありません。なぜなら、偉大なイノベーターになることが私のカルマだとは思っていないからです。つまり、今よりも良いプレーをしたいし、今よりも良いプレーを続けたいと思っていますが、どのようなツールを使用しなければならないかについても現実的になる必要があります。私が何を言おうとしているのかを非常に明確にしておきたいと思います。私は自分がイノベーターだとは思っていないので、人々が私をイノベーターだと言うと少し不快になります。

BM: 私は子供たちにあなたの真似をするよう勧めているだけです…

DS: なぜなら、私は彼らが聞いている通りだからです。

BM: そうですね、でも彼らはあなたの真似をしているかもしれません…

DS: それが彼らに聞こえるすべてだからです。彼らはラジオでチャーリー・パーカーの声を聞きません。

BM: でも、場合によっては、音楽学校を出た野心的な子供たちが、ビルボードを読んであなたのアルバムがチャートに入っているのを見て、あなたの真似をしようとするかもしれません。

DS:みんな私を見て、「この男はそれで金を稼いでいるから、私も彼のように演奏して大金を稼ごう」と言うんです。ええ、それも大いに関係していると思いますし、それがやる気をなくさせるんです。「確かにチャーリー・パーカーは素晴らしいけど、今どこにいるんだ? 家賃をなんとか払わないといけないし」って感じですね。ええ、それはちょっとやる気をなくさせるんです。だから、ウィントン・マルサリスのような人が現れて、「この音楽を演奏して生計を立てられる」と言ってくれたのは素晴らしいことだと思います。彼はその姿勢で多くの若い演奏家たちを刺激しただけでなく、レコード会社が「この音楽を聴いている人たちがいる。レコードを買っている人たちがいる」と言えるような現実を作るのにも貢献しました。実際、実際にそうなっています。でも、そういう金銭的な側面全体が、自分の仕事の原動力にはなり得ません。つまり、私が今やっていることは、それが理由ではないし、それが始めた理由でもないんです。私はビジネスを始めたわけではありません。音楽が好きだったのでミュージシャンになりました。ビジネスという部分は後から出てきたものです。他の人と同じように生計を立てなければならないからです。私は自分のやっていることで十分な収入を得ることができ、とても幸運でした。でも、私は豪邸もリムジンも持っていません。何百万枚もレコードを売っているわけではありませんが、まあまあです。家賃はここで払われていますが、ここは宮殿ではありませんし、家賃が安定した建物に15年間住んでいるので、家賃はかなり安いです。でもサックスが10本ありますし、移動も自由です。レコードを作って、ツアーに出て演奏することもできます。チャンスがあります。私にとって、それが最大の報酬です。それが成功の具体的な報酬です。外に出て音楽を演奏し、レコードを作る余裕ができることです。他のすべてはおまけです。クリスマスに数千ドル余分にもらって、誰かに特別なプレゼントを買ったり、別の楽器を買いたいと思っても、事前に考えなくてもいいなら、それは素晴らしいことです。「そうだ、新しいアルトが欲しい」と言って、それを買ってしまうのです。でも、私はもう長い間これをやっています。私は43歳です。30代になるまで、自分でレコードを作ったことすらありませんでした。そして、ここ数年までは経済的に本当に成功したわけではありません。

BM:あなたが作っているものについて、多くの誤解がありますか?

DS:よくわかりました。私はよくジャズ・プレイヤーから、金を稼いでいると思ってるような態度をとられていたんだ。つまり、私が信じられないほど裕福だと思っている人もいるということです。さてケニー・G…彼は大金を持っていますが(笑)、レコードは250万枚売れた。僕はそういう数字は売れない。そんな金稼いでいませんよ。

BM:アルバム・ジャケットの顔を見ると、すぐに金持ちだと思われがちです。

DS:ええ、そういう連想はあります。テレビに出ているのを見たら、そんなことは忘れてください。テレビに出たら、「この男はロサンゼルスに家を持っていて、パークアベニューに住んでいて、リムジンと女たちもいる」などと言われるでしょう。でも、それはすべて幻想です。だから今は、自分の優先順位を変えて、成功の仕組みにとらわれないようにしています。なぜなら、それはとても魅惑的だからです。「さあ、これをやれば売れる」と言いたくなる衝動。それをやると、内面が死んでしまうからです。皮肉なことに、音楽的に死んでしまうと、商業的にも死んでしまうのです。私はそれを信じています。その点では私はナイーブなのかもしれません。でも、長期的に見れば、商業的であることの本当の意味は、自分らしくあり、人々がそれを買ってくれることを願うことだと本当に信じています。しかし、人々が何を好むかを計算し、何を買う可能性があるかを考えながらそれを実行すると、失敗することになります。

BM:トレンドは2年ごとに変わります。

DS: それだけではありませんが…なぜこんなことをするのでしょうか?手っ取り早く大金を稼ぎたいなら、商品トレーダーになってみてはいかがでしょうか。つまり…音楽には手っ取り早く簡単に儲かるお金がたくさんあると思います。そのようにすることは私には思いつきませんでした。私は25年間ミュージシャンとして活動してきましたが、たくさんのことを経験してきました。私は何度も失業してきました。ご存知のとおり、私も家賃などを支払うのに十分なお金がなかった時期がありました。私はそれを経験しました。そして、そのようなプレッシャーが毎月かかってくるのは絶対にやめたほうがいいでしょう。しかし、それを和らげることが必ずしも人生を良くするとは限りません。本当に好きなことをやっているのであれば、お金がないことは些細な不都合に感じることもあります。確かに、生計を立てなければなりませんが、それが好きだから[音楽を作る]ことをしなければなりません。そして、好きな音楽を演奏しなければ意味がありません。自分のやっていることに気をつけなければなりませんね?そして、大金を稼ぐためには、単なる計算された方法以上のものでなければなりません。楽しんでください。そして私はそれを楽しんでいます。

BM:そして、この変化はあなたが経験しているのですか?

DS: 早期警戒システムを持っています。自分が間違った方向に進んでいると感じ始めたら、休憩を入れます。ですから、必ずしも自分の行動に不満があり、それが「よし、今が変える時だ」と言うわけではありません。ただ、「ああ、この先に岩があるな」と感じるだけです。「少し道を外して、よく考えたほうがいいよ。」そしてそれが私が今いるところだと思います。

写真提供者: Alice Soyer

==============================

A Fond Reminiscence of David Sanborn

The alto sax great, who passed away on Sunday at age 78, was the subject of a Downbeat cover story I wrote in 1988 at a time when he was at an artistic crossroads

BILL MILKOWSKI [Musings on Music by The Milkman]

MAY 14, 2024 https://billmilkowski.substack.com/p/a-fond-reminiscence-of-david-sanborn?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

photo by Alice Soyer

In 1975, Milwaukee’s premier fusion band, Sweetbottom, was covering just about every track off of David Sanborn’s popular new solo debut, Takin’ Off. I remember their renditions of Steve Khan’s “Butterfat” and “Duck Ankles” from that album went over particularly well with the sophisticated crowds that packed Sardino’s Bull Ring, Ltd. every week to hear Sweetbottom play.

Butterfat · David Sanborn

Taking Off ℗ 1975

https://youtu.be/rZcbic0FjWA

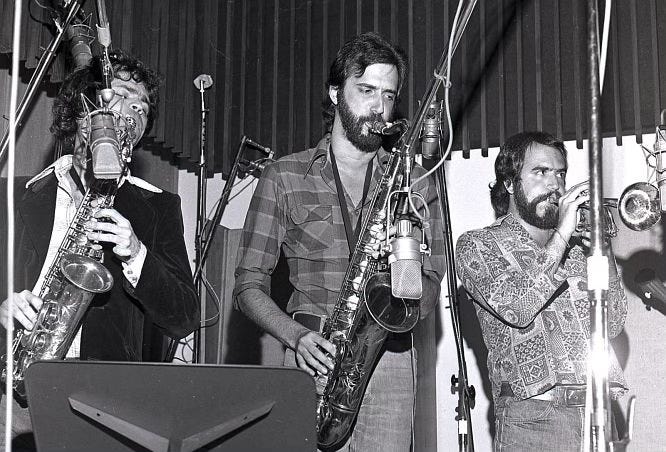

That same summer on ‘75, the airwaves were burning up with David Bowie’s “Young Americans,” which showcased Sanborn’s signature alto sax licks. Right on the heels of that release came the Brecker Brothers self-titled debut, which featured Sanborn’s alto alongside Michael Brecker’s tenor sax and Randy Brecker’s trumpet.

Sanborn’s familiar alto cry also appeared that year on Paul Simon’s Still Crazy After All These Years, Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run, the Eagles’ One of These Nights, The Manhattan Transfer’s self-titled debut and James Taylor’s big radio play hit, “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)” as well as on the fusion landmark, Beck & Sanborn.

Joe Beck & David Sanborn – Spoon’s Theme

https://youtu.be/FxgdlIOa2bU

The following year, David’s alto sax could be heard on Jaco Pastorius’ funky “Come On, Come Over” from the bass phenom’s 1976 self-titled debut as well as on Mose Allison’ Your Mind Is On Vacation, Michael Franks’ The Art of Tea, Phoebe Snow’s Second Childhood, George Benson’s Good King Bad, the Brecker Brothers’ Back to Back and Ian Hunter’s All American Alien Boy. Then 1977 saw the first of his collaborations with Bob James on Heads, while he also appeared on James Taylor’s JT, Don McLean’s Prime Time and Gil Evans’ Priestess (featuring Sanborn playing an absolutely monumental solo on “Short Visit”).

Gil Evans – 2. Short Visit

https://youtu.be/4kqLbppLEuo

He also released his mega-selling third album, Promise Me the Moon, that year. Little did I know, I had already heard him in the horn section on records by the Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band (1968’s In My Own Dream), Muddy Waters (1969’s Fathers and Sons), Stevie Wonder (1972’s Talking Book), The Eagles (1972’s Take It Easy) and B.B. King (1972’s Guess Who) and Todd Rundgren (1973’s A Wizard, A True Star). Sanborn owned the ‘70s.

From 1988 to 1990, Sanborn hosted the eminently hip tv show, Night Music. Every Sunday night, an eclectic mix of guests was paraded across America’s tv screens, with Sanborn not only providing informative introductions but also sitting in with the bands. Here’s a rundown of just some of the incredible artists who appeared on Night Music during it’s run: Bootsy Collins, Sting, Eric Clapton, Rufus Thomas, Joe Cocker, Allen Toussaint, Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Pharaoh Sanders, Phil Woods, James Taylor, Van Dyke Parks, Slim Gaillard, Eddie Palmieri, Dr. John, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Mavis Staples, Sam Moore, Ashford & Simpson, Milton Nascimento, Jack Bruce, Bill Frisell, Al Green, Elliott Sharp, John Zorn, Pops Staples, John Hiatt, Curtis Mayfield, Abbey Lincoln, Marianne Faithfull, Phoebe Snow, Fontella Bass, Aaron Neville, Al Jarreau, Leonard Cohen, the Kronos Quartet, his personal alto sax hero Hank Crawford and dozens more. And Sanborn not only sat in with all of them, he more than held his own in each setting.

Pharoah Sanders, David Sanborn, Night Music — ‘Thembi’

https://youtu.be/uTNR9hOR7ok

Sonny Rollins and David Sanborn play “Kim” – Live on Night Music – 1989

Taken from Night Music 119

https://youtu.be/hBARGhakXLw

Phil Woods and David Sanborn from Night Music, 1988

https://youtu.be/wAEdeXpVcpo

Sting – Bill Frisell – Dave Sanborn – Don Alias – Aint No Sunshine

Night Music 1989

https://youtu.be/zC2fPLxocHU

Eric Clapton – Hard Times

Night Music with David Sanborn

https://youtu.be/cGCxo2HLuYA

Hank Crawford playing “The Peeper” on Night Music

https://youtu.be/o0Cx8Tk4Miw

John Zorn, David Sanborn, Marcus Miller – Snagglepuss – 1988, Live @ Night Music

https://youtu.be/UXYkSlG9kcw

‘Night Music’ (‘Sunday Night’) show, season 1, episode 7, which went on NBC channel in 1988.

Curtis Mayfield – Pusherman [Sunday Night Live 1989]

https://youtu.be/6dTSIXcfT3U

Rufus Thomas – Walkin’ the Dog [Sunday Night Live – 1989]

https://youtu.be/BmLTAfUkAJ0

Bootsy Collins & Pretty Fat – Stretchin’ Out [Night Music 1990]

https://youtu.be/WNMJEvxqj_g

My first interview with Sanborn for the August 1988 issue of Downbeat, in which he pondered about getting caught up in the seductive machinery of success (see below), took place at his apartment on the Upper West Side of New York. Years later, I conducted a joint interview him and Bob James in conjunction with their 2013 release, Quartette Humane (with Steve Gadd and James Genus). Most recently, he generously shared some very insightful (and hilarious) commentary about Michael Brecker for my 2021 book, Ode to a Tenor Titan: The Life and Times and Music of Michael Brecker (Backbeat Books). When I got word of his passing this past Mothers Day (Sunday, May 12), the news hit like a ton of bricks. He was a sweet man with a genuine smile, a quick self-deprecating wit and an instantly recognizable sound on his instrument. R.I.P., David

You recognize it in an instant—the Sanborn squeal. Couldn’t fool anybody on a Blindfold Test with that. Or could you?

So many Sanborn clones have come pouring out of the closet of late, appearing on everything from pop-jazz fare to jeans commercials on tv, that it’s getting harder and harder to tell the ripoffs from the real deal. A cursory twirl of the radio dial or channel selector might suggest that every commercial musician and would-be alto star out there is aping Sanborn’s sound. But if you take the time to really listen, you can hear the truth.

This is a situation that both befuddles and frustrates Dave. Of course, it’s happened over and over again throughout the course of music. There have been Bird clones, Wes clones, Charlie Christian clones, Trane clones, Jaco clones. But the humble Sanborn refuses to think of himself in the same company with those jazz greats. In fact, he’s not comfortable being called a jazz musician at all. Suffice it to say, the man is confused. On the eve of his 11th release for Warner Bros. — the typically funky, hard-blowing and eminently well-crafted Close-Up (produced by Marcus Miller, co-produced and engineered by Ray Bardani) — Sanborn confesses, “I don’t know what’s happening to me right now. I dunno . . . maybe it’s midlife crisis, maybe I just need to make a clean break, make a change. I’m just at a point now where I’m kinda reassessing what I do. I’m going back and listening to a lot of music, mostly bebop. I’m working a lot with Nicholas Slominsky’s Thesaurus Of Scales And Melodic Patterns. I’ve got some Mozart flute duets, I’ve got an Oliver Nelson book, the Joe Viola Berklee books, a couple of fake books. I guess I’m just doing research, is what it comes down to. Just shedding.”

There are long pauses between sentences, occasional sighs. Clearly, the man is at odds with himself. What will come out of this sudden change of heart is uncertain. He hinted at getting away from the technology of drum machines and studio manipulations by embracing an all-acoustic context, maybe record something live in the studio like in days of yore. But that’s just thinking out loud. Maybe this frame of mind will pass. Maybe Dave just had a bad day/week/month/year. Whatever the reason, he’s suddenly second-guessing his direction, though you couldn’t tell it from listening to Close-Up. Sanborn blows with typical conviction and fire on funky fare like “Slam”, “J.T.” and “Pyramid.” And the signature Sanborn squeal is back in full force on such soul-stirring ballads as “Goodbye,” Randy Newman’s melancholy “Same Girl,” and the hit pop love song of some years ago, “You Are Everything.” In short, another hot Sanborn album, destined to sell well.

We spoke in Dave’s Upper West Side apartment in Manhattan a day before he split for London to perform at a birthday bash for Nelson Mandela.Meanwhile, he continues to make regular guest appearances on the Late Night With David Letterman Show, featured in the house band alongside Paul Shaffer, Will Lee, Anton Fig and Sid McGinnis. And he continues to broadcast his weekly program, The Jazz Show, which is broadcast on the NBC radio network. Down the road, there are plans for Sanborn to co-host a fall television program with Saturday Night Live regular, Dennis Miller. This music and comedy show, to be seen on Sunday evenings beginning in late September, is tentatively called Sunday Night. Besides sharing banter with Miller and other guests, Sanborn will lead the house band that (as of this writing) will include such formidable talents as bassist Marcus Miller, drummer Omar Hakim, guitarist Hiram Bullock and keyboardist Don Grolnick. But that’s down the road. For now, Dave’s got some things to get off his chest.

BILL MILKOWSKI: Talk about establishing a voice on one’s instrument.

DAVID SANBORN: Yeah, that’s one of the great things about music, to me. It’s somebody’s personal statement. Ultimately, that’s what you end up with. You refine your craft but the object is to express yourself. And if you’ve got nothing to express, you have no character, no humanity to express, then what good is all the technique?

BM: So how do you feel about yourself in that regard?

DS: I have no technique and I’m rapidly losing my personality [laughs]. I don’t know what’s happening to me right now. I’m going through a transition that I don’t quite understand; so, consequently, I can’t articulate it very well.

BM: But you’ve made your mark over the years in the sense that your sound is immediately identifiable.

DS: I guess I…and I don’t mean to be naive or humble about it, you know, but I guess I have. And it’s a little bit uncomfortable for me to think about that because I don’t think of myself as an innovator, in the slightest. I think when people tell me that, it’s harder for me to grasp what that means. I mean, I think more than anything else, I just happened to be the only guy around playing alto in mostly a pop and r&b idiom during the early ’70s. And I think that because of the exposure that I got through David Bowie [YoungAmericans] or Stevie Wonder [TalkingBook] or James Taylor [“How Sweet It Is”] or Bruce Springsteen [Born To Run], I was very lucky. ’Cause I’m not doing anything new. I never was doing anything particularly new or innovative. I was just distilling a lot of my influences. You know, I was always trying to sound like Cannonball or Phil Woods or Jackie McLean or Hank Crawford or other people I greatly admired.

David Sanborn at age 16 playing in St. Louis with some experienced vets on the bandstand

BM: But you established something, a signature quality. I never really cared for David Bowie that much until that sax in “Young Americans” caught my ear. Not the line so much as the sound.

DS: Well, I think that’s what you try to do as a player, in any form of self-expression, you find yourself. You refine your craft but whatever comes out is you. And when I say I tried to sound like Cannonball, what I meant was I would listen to him and emulate that quality, that energy. I couldn’t try to play those licks because I couldn’t do that. That wasn’t me. It’s like the reason I’m not a bebop player, necessarily. I mean, I can affect some of the mannerisms of bebop and I relate to the time feel and I understand a certain amount of it, but me trying to play that is, like…why? You step out of your idiom, your focus of expression, to learn. You do those other things to learn, to grow. But what you come back to is your…I don’t want to use the word “art” because I don’t necessarily think of what I do as art.

BM: It’s your voice.

DS: Yeah, you come back to your voice. And whatever avenue you choose, whatever you have to say to the world, it comes down to that basic thing. It’s your own voice, whether it’s as a painter, a sculptor, a writer. It’s like Hunter S. Thompson or John Updike or whoever. It’s their voice, their point of view. And in a more abstract way, that’s what music is — somebody’s point of view about the world. It’s all their influences, and you can maybe hear all the influences. But you distill all those influences and they come through, hopefully, in a very subconscious way. They make you what you are and they give you a connection to the tradition. But your voice is your point of view about that tradition.

BM: And once you find your voice, it becomes a question of application, the context. And that could be a difficult decision these days, given all the avenues you could take, not to mention the pressures that come to bear on artists from record companies.

DS: It can be a trap, in a sense. It’s what happens to a lot of sidemen when they finally make their solo record, or to studio players. All of a sudden they say, “Hey, I can do this and that and this over here.” Well, that’s fine, but what about YOU. I know you can play jazz and rock and r&b and whatever, but where are YOU in all of that? So I think it’s important to create the context, whether you actually create it physically or just generate it like a Miles Davis does. I mean, Miles doesn’t write music but he does create music. There’s no doubt that during the period when Wayne Shorter was writing all the music for Miles that it was still indeed Miles’ music. Even though Wayne wrote it and provided the raw materials, Miles shaped the context. And I’ve had that experience in the few times that I’ve worked with Miles. Same with Gil [Evans]. They’re both arrangers creating a context for the voices. When Gil did the arrangements with Miles for Porgy And Bess, they became Gil’s arrangements even though in a lot of cases what he did was just orchestrate Gershwin’s piano score. He told me that. But it’s how he orchestrated it, how he shaped the music that made it his personal statement. And the fact that he chose that particular score also helped to shape the context. It’s all of those things that go into it. There’s a lot more to playing than just playing. And it’s…I think I’m just having to re-evaluate the whole thing, the whole process, for myself right now.

BM: And what things are you thinking about?

DS: Just kinda getting a sense of what I want to do for myself from now on. I don’t want to think about what I’d do in an idiom. It seems like what I’m doing has become very stylized, as a result of my own actions and as a result of other people imitating me. I mean, it’s a little disconcerting to hear them. And in a lot of cases these guys play better than I do, with a lot more technical facility than I have. I hear some people who have my sound with Mike Brecker’s technique [laughs]. And they’re good players and I guess I should be flattered that people consider me an influence, just in terms of sound. I think that’s really where my influence has been on players, with the sound.

BM: While you may be flattered, you’re also leery of that whole copycat trip.

DS: Yeah, I don’t wanna listen to that stuff too much, you know? It’s a little distracting sometimes, but I don’t dwell on it. I don’t say to myself, “Well, gee, I gotta sound different now.” It’s all kind of funny to me, especially when I hear somebody copy mistakes I’ve made on record. There’s a guy who…I won’t mention his name…I shouldn’t actually say this…naw, forget it.

BM: There have been hordes of sax players who have imitated, or tried to imitate, John Coltrane or Charlie Parker.

DS: Well, how can you be a tenor player and not be influenced by John Coltrane or be an alto player and not be influenced by Charlie Parker?

BM: By the same token, how can you be an aspiring alto player in 1988 and not be influenced by David Sanborn?

DS: Yeah, but the difference is that Charlie Parker was an innovator and a genius whereas I’m just…I have a style of playing. Charlie Parker was an innovator rhythmically, harmonically, melodically. He revolutionized the instrument. And music. And, I mean, I’m closer to somebody that sort of came up with an interesting sound, and I was lucky enough to make a living with it and to have people want to hire me so I could play and continue to learn how to play my instrument better. But I think it would be a…I mean, it’s not even in the same…you can’t even say me and Charlie Parker in the same breath because there’s an abyss there between what he did and what I did. I just have a pleasing kind of sound and a style that happens to be…I’m not in any way an innovator. And I’m not putting myself down because I don’t think that’s my karma, to be a great innovator. I mean, I’d like to play better than I do and I’d like to continue to play better than I play now, but I also have to be realistic about what are the tools that I have to work with. I want it to be very clear what I’m trying to say. I get a little uncomfortable when people say that I’m an innovator, because I don’t think I am.

BM: I’m just suggesting that kids emulate you…

DS: Because I’m what they hear.

BM: Right, but they might be emulating you…

DS: Because that’s all they hear. They don’t hear Charlie Parker on the radio.

BM: But in some cases, ambitious kids coming out of conservatories may choose to emulate you because they read Billboard and see that your albums are charting.

DS: They look at me and say, “Here’s a guy who’s making money doing it so I’m gonna sound like him so I can have a lot of money too.” Yeah, I think that’s got a lot to do with it too, and that’s discouraging. It’s like, “Sure, Charlie Parker’s great, but where is he now? I gotta pay my rent somehow.” Yeah, that’s a little discouraging, which is why I think it’s great that somebody like Wynton Marsalis came along and said, “You can play this music and make a living.”And he not only inspired a lot of young players with that attitude but he also helped to create that kind of reality for the record companies to say, “Well, people are listening to this music. People are buying these records.” And they are, and they do. But that whole financial aspect cannot be the primary motivating force behind what you do. I mean, that’s not why I’m doing what I’m doing. That’s not why I started. I didn’t go into a business. I became a musician because I love the music. And the business part is what came up later, because you have to make a living like everybody else. And I got very lucky because I was able to make a good living doing what I’m doing. But, I mean, I don’t have a mansion and a limousine. I don’t sell millions of records, but I do OK. My rent is paid here but this is not a palace, and I’ve been living here for 15 years in a rent-stabilized building so my rent is fairly low. But I’ve got 10 saxophones and I’ve got mobility. I can make records and go out on the road and play. I have opportunities. And that, to me, is the greatest reward. That’s the tangible reward of success: being able to afford to go out and play music and make records. Everything else is gravy. If you get an extra couple of thousand dollars for Christmas to buy a special gift for somebody, or if you wanna buy another instrument and you don’t have to think about it before you do it, that’s great; to say, “Yeah, I want that new alto,” and take it. But I’ve been doing this for a long time. I’m 43 years old. I didn’t even make a record on my own until I was in my 30s. And I haven’t really been economically successful up until the last few years.

BM: There are a lot of misconceptions about what you‘re making?

DS: I get it all the time. I used to get it from jazz players who would have an attitude about me because they thought I was making all this money. 1 mean, some people think I’m incredibly wealthy. Now Kenny G…he’s got a lot of money [laughs], but he sold 2.5 million records. I don’t sell in those kinds of numbers. I don’t make that kind of money.

BM: People see a face on an album cover and right away assume the guys rich.

DS: Yeah, there’s that association. And when people see you on tv, forget about it. If you’re on tv they’ll say, “This guy’s got a place in LA, he lives on Park Avenue, he’s got limos and bitches,” you know, the whole nine yards. But, it’s all fantasy. So right now, I’m rearranging my priorities and not getting caught up in the machinery of success, because it’s so seductive. You know, the urge to say, “Well, let’s just do this and it’ll sell.” Because when you do that, you die inside. And the ironic thing is if you die musically then you die commercially too. I believe that. Maybe I’m naive in that regard. But I really believe that the true sense of being commercial in the long run is to be yourself and hope that people will buy that. But if you go into it thinking about trying to calculate what people are going to like and trying to figure out what they might buy and then you go and do that, then you’re screwed.

BM: Because trends change every two years.

DS: Not only that but…why do this? Why not go out and be a commodities trader if you wanna make a lot of money quick. I mean…I guess there is a lot of quick and easy money in music. It hasn’t occurred to me to do it that way. I’ve been a working musician for 25 years and I’ve gone through a lot. I’ve been on unemployment a lot. You know, I’ve had times where I didn’t have enough money to pay the rent or whatever. I’ve gone through it. And it’s definitely better not to have that kind of pressure hanging over you from month to month. But relieving that doesn’t necessarily make your life better. Sometimes if you’re really doing something that you really love, being broke can be a minor inconvenience. Sure, you gotta make a living, but you gotta do this [make music] because you love it. And you gotta play the music you love or there’s no point to it. You gotta care about what you do, you know? And it has to be more than some calculated way to make a lot of money. You gotta enjoy it. And I do enjoy it.

BM: And this change you’re going through?

DS: I have an early warning system. If I get to the point where I start to see that I’m going in the wrong direction, I put the breaks on. And so, it’s not necessarily something that 1 do that I’m dissatisfied with that causes me to say, “OK, now it’s time to change.” It’s just that I sense that, “Oh oh, there’s some rocks up ahead. I better pull off the road a little bit and think this over.” And that’s where I’m at now, I guess.